- Paul Lambie:

- Aaron [Renn] says that the government shouldn’t try to sign “gotcha” deals with private parties, but does anyone believe that the aim of private entities is not to take advantage of government officials with such deals?

- @vruba:

- Here’s the thing. Wealth is not a number of dollars. It is not a number of material possessions. It’s having options and the ability to take on risk.

- Cynthia Kaufman:

- The idea that human nature is unchangeable and that it is basically selfish or anti-social is used over and over again to discourage people from challenging our current social order. It is one of the mechanisms used to promote cynicism and destroy hope.

- OnUp:

- I have to: (shoot this Rhino / suck this dick / deal this crack / rob this house / mug this person / run this racket / flip this cheeseburger / add micro transactions to this game / deny this claim / drill this deep ocean well / keep working for this !@#$%ing company / …(List_1))

- In order to: (aquire money / feed my children / attract a relationship / give myself and my family a decent quality of life / …(List_2))

- fcecin:

- [Universal basic income] raises the “temperature” of the collective economic body. The barrier for people getting together and doing grassroots and idealistic work, anywhere — all the work we already have been brewing for decades — suddenly lowers from a 100 ft brick wall to a cute 1ft white wooden fence.

- Cathy O’Neil:

- I’m a sucker for reverse-engineering powerful algorithms, even when there are major caveats.

- JenniferP:

- Sometimes you have to take a job that you know will be a bad fit because you would prefer eating to not eating. Never, and I mean never, feel like you have to defend or justify that choice.

-

Quotebag #113

-

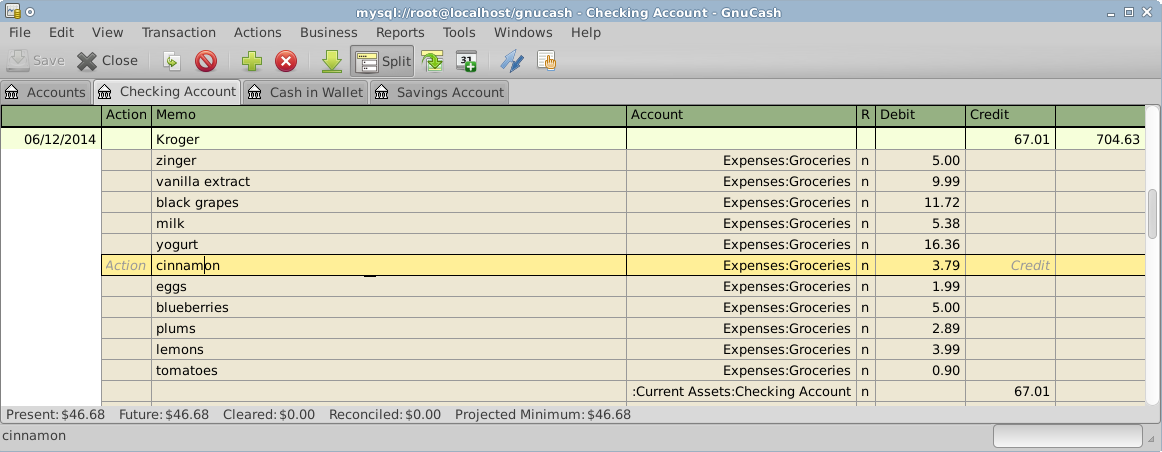

Thingcentric accounting

In conventional accounting software such as GnuCash, a dupermarket receipt might be entered thus:

A particular line item in the receipt, say the cinnamon, is charged to a certain account, and that account is debited by the $3.79 price of the cinnamon. The credit side of the transaction is to the checking account; a portion of the $67.01 total. In thingcentric accounting as I propose it, the cinnamon purchase is not treated as a line item in a transaction covering a shopping cart full of merchandise, but a transaction that takes place when the cinnamon is added to the cart:epoch thing valuation credit account debit account 1402597800 Spice Islands® ground saigon cinnamon, 1.9 oz. glass jar 3.79 Liabilities:Accounts Payable:Kroger Assets:Inventory:Food:Dry Goods:Seasonings The accounts payable credit will be cancelled at the cash register. The main difference is that we’re moving from debit and credit amounts to credit and debit accounts, respectively. Note that I put credit account on the left and debit account to the right. This is because I think of them as “from account” and “to account,” respectively. At the time we open the jar of cinnamon, we enter a transaction “from” inventory “to” an expenditure account appropriate to cinnamon.

In this system, inventory accounts in general are intended to be shared information. This is so we can do “internet of things” and hopefully do so without the middlecritter (i.e. do so cooperatively as contrasted with commercially). It should be able to answer questions like “where is the nearest X” that is in the possession of someone in the network of participants. I’m thinking network because I’ve been looking at ValueNetwork, the accounting platform for networks. This would be most straightforward if inventory is geotagged, but with that there is a privacy and security issue in that information about the presence of valuables in private homes is revealed. This brings us to the co-opted version of “sharing economy,” whose cheerleaders point out that transactions can take place between individuals, cutting out som(bunall) middlecritters. The middlecritter still standing is the “reputation metric provider,” an industry that almost overnight has produced at least one billion-dollar fortune. The reputation engine itself is decidedly closed-source, encumbered by as many copyrights, trademarks and patents as can be secured, and of course has all the information monetization schemes to be expected of commercial mobile apps in general. It is also becoming clear that information asymmetry is a key ingredient in the business model, in which criteria for exclusion and perhaps blacklisting are closely-guarded trade secrets. The key to a “disruption” in the form of the “sharing economy killer” that we all want is DIY reputation metrics in a way that is open source and open content. If our reputation engine can also offer respect for the privacy of individuals, I guess that would be the icing on the cake.

One approach might be to conceal actual spatial coordinates of a particular inventory item, but allow queries of along the lines of: “Is there an X within Y km of location Z?” Such queries might trigger notifications to the custodians of inventory found by the query; possibly initiating a sequence of messages resulting in the transfer of the goods. Another approach might be to forgo privacy altogether and shore up security through equiveillance. Surveillance cameras that are webcams; one in my pantry seem less privacy-invasive than one in my bathroom. Considerably more importantly, a camera under my auspices seems less privacy-invasive than one under police auspices, landlard auspices, etc. Also, access by the general public to information about my pantry seems less invasive than use of the same information by analytics providers who would use the information strategically, say to deduce or infer my internal price point for certain products.

If we set this up so that inventory accounts are property of the network, then purchases of goods by individuals constitute contribution of dollar-denominated value to the network. Consumption of goods (transfer out of inventory) is of course taking money from the network. There should be a way in which the question of whether someone is putting at least as much value into the network as they are taking out of it that is independent of where the acts of giving and receiving take place, and independent of which inventory custodians are dispensing the goods.

At this point what we have is an actually-sharing-economy that covers distribution of goods created in the actually-existing economy. Bringing the thingcentric accounting to household or cooperative production will of course be in most cases illegal and is where “agorism” comes in, and perhaps Bitcoin, as the authorities will demand not only taxes but licenses. The black-market nature of agorism definitely competes with the goal of extreme transparency. Extreme internal (but only internal) transparency would mean joining rather than beating the black-box “sharing” economy of Über, AirBnB, ad nauseam. The established-so-far simulacrum of sharing economy is heavily “disruptive” to licensing bureaucracy but minimally if at all disruptive to other forms of rent-seeking, such as intellectual property. An even bigger challenge at this point is keeping things anagoristic (non-market oriented). What goes into the “valuation” column once labor inputs are in play? Do people self-valuate? Letting the market decide somewhat defeats the purpose (at least one of them). The most important thing to accomplish is to establish such an act of creation as a process or graph node in an Angel Economy, or perhaps recipes in a ValueNetwork implementation. Eventually we want to have not only an inventory of things in possession of the network, but a catalog of things the network is known to be capable of producing.

-

Is Value Network relevant to Angel Economics?

I suspect the architects of Value Network (“ERP for networks”) have stumbled into some of the same concepts that I did when expanding on Angel Economics:

My first suggestion was to start with a simple production process; organized around one person or some other small number. Identify the inputs and outputs of that process. This activity should be simple, step-by-step and replicable.

In Value Network there is a data schema for modeling economic activity. What stands out to me is that they refer to one of the basic units of economic activity as recipes. Combine that with Value Network being about networks of economic actors, and it becomes clear that Value Network and Angel Economics have much in common. I want to connect with this community, and it looks like their Github presence might be a venue for that, but I don’t know how to approach them. (Hell, I don’t even know how to approach Github, and I understand that’s a common gripe…) Suggestions (or even introductions) would be welcome.

-

What is a “foundup?”

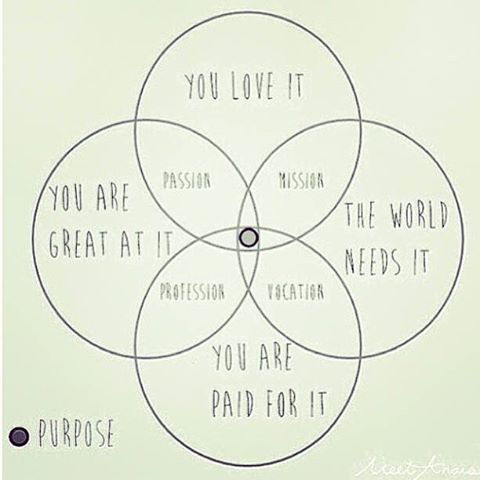

I saw this mandala-like Venn diagram on Facebook:

The Venn Diagram partitions the plane into 14 regions. There are of course 16 possible subsets of the four elements. The two are excluded from the diagram (but hopefully not excluded as possibilities) are

- You are great at it

- The world needs it

- You don’t love it

- You aren’t paid for it

and the complementary scenario:

- You are not great at it

- The world doesn’t need it

- You love it

- You are paid for it

The first of these scenarios identifies by the Venn Diagram as “impossible” might apply to a soldier, probably not in the modern world in which it’s assumed in all but the most tragic countries that soldiers should be paid, but perhaps the “warrior saints” of early Christian history would be historical examples. Maybe the Guardian Angels would be a contemporary example, but I don’t know. The second unacknowledged combination is the territory occupied by a large percentage of those people known as celebrities.

Certain regions of the diagram are associated with certain qualities:

- greatness+love=passion

- love+necessity=mission

- necessity+remuneration=vocation

- greatness+remuneration=profession

I suppose we could add

- necessity+love=dedication

- love+remuneration=promotion

As for foundups, I’m not sure. I don’t know whether to think it’s just a well-intentioned pyramid scheme, or something far-reaching and VACIMET-like.

-

Moving the goalposts is not a victimless crime

As we contemplate the slow, painful, but hopefully forward progress from the merely voluntary to the snarkily-defended “euvoluntary,” to the thickly voluntary, to the actually palatable, let’s re-visit a concept introduced by the labor movement: the scab. The scab is someone who crosses a picket line. By doing so, they make things worse for everyone by lowering the standards to which an employer can realistically be held. Yet another example of how the “any job is better than no job” “ethic” is at best an inducement for good people to do bad things.

The word “scab” comes to my mind in reference to a vast array of human actions in addition to people crossing picket lines. Sometimes I’m so expansive in my definition of scab that it means “doing something I wouldn’t do,” or even “doing something I wouldn’t be proud of doing.”

The word “scab” comes to my mind in reference to a vast array of human actions in addition to people crossing picket lines. Sometimes I’m so expansive in my definition of scab that it means “doing something I wouldn’t do,” or even “doing something I wouldn’t be proud of doing.”As an agitator for radical social change, my biggest frustration in life is a basically passive attitude toward private and public institutions on the part of a sizable share (normally a majority) of the population.

The gravity of these random acts of scabbiness ranges from petty annoyances like people who gripe about each Facebook policy change but don’t leave Facebook, to the mere existence of people literally working for pennies via Mechanical Turk. Just creating proof of concept for a race to a point that close to the bottom seems to me to cross the line from scabbiness into outright class treason.

Lest I be too judgmental…

Like probably everyone, I am guilty of many instances of shameful, scabby conduct. Since my own life expectations have largely been a case study in moving the goalposts, my excuses are likewise pathetic. Instead of the Yuppie Nuremberg Defense (“I’ve got a mortgage”) I’ve been whittled down to the Precariat Nuremberg Defense (“I need the experience”).

Funny how experience gets treated as a scarce commodity regardless of whether you’re buying or selling.

Solidarity, folks. Solidarity.

-

Quotebag #112

There is no article of faith more fancifully supernatural than belief in a natural free market.

Because when people are living on the bleeding edge, at the absolute lowest cost of existence in this society, then occasionally things are going to go wrong and the person is going to run out of money.

The elite is composed of generally smart people with servants who are either useful idiots or who have narrowly circumscribed interests/intelligence. But they are not geniuses. Elite machinations seem complex and hard to think about because the vast majority of the public is not involved in them, is not aware of the details and calculations made. Elites simply know their own business and interests and we generally do not.

The division between the commercial sector and the public sector might be a convenient rhetorical choice, but it is incoherent as an analytical framework through which to understand the politics of a surveillance society.

Nobody gets to decide who’s being poor correctly.

Education, skills and experience cannot compete with the network.

In their article, Taylor and Appel wonder if it is “time to ask whether education alone can really move people up the class ladder.” With all due respect, that is the wrong question. It is time to ask whether or not there should be a ladder. And the answer is no.

-

Police is a verb

Privatizing the police does not constitute abolishing the police. Anarchy refers to an unpoliced population, not a privately policed one. If anything, the accountability-in-theory of a local police department to the community at large is a lesser evil (though still of course an evil) than the accountability-in-practice of a security firm to its paying customers.

Unrestrained human nature is basically safe, or it is not, in which case you are a statist.

-

Nonproprietary cities

Not sure if it’s a trend, but I’ve recently noticed what seems to be a shift in terminology from “charter cities” to “proprietary cities.” I’m also not sure whether these terms are supposed to be synonymous. Nevertheless, it seems that a charter city or a proprietary city is an attempt at an end run around territorially defined constituted authority, intended to produce proof of concept for, if not anarchy, at least polyarchy. The proponents of such cities by either name seem to be pro-capitalist libertarians ranging from ultra-minarchist to anarchist.

This raises the question of whether creation of ungoverned local communities ex nihilo is a tactic deserving the consideration of anticapitalist (i.e. antilibertarian) antistatists. For ecological reasons, I have deep reservations about breaking ground to create alternative communities. Reorganizing existing communities along ideological lines seems like a type of hostile takeover, unless the agenda for change originates in a broad (if not unanimous) consensus of the residents of a community. In the case of charter cities, one of the most frequently-proposed sites of late has been Honduras, which has suffered(?) the convenient disaster of a coup d’état. It’s quite reminiscent of the 9/11 (1973) coup in Chile that created a power vacuum conveniently made available to be filled by free market principles. A leftist attempt to create a non-statist city should reflect leftist values, which means less opportunism and a need to work within existing normative constraints. These constraints, like it or not, include the institution of property, but there may be a way to turn this to our advantage.

I propose referring to the left wing alternative to the proprietary city as a nonproprietary city.

I suggest we work within capitalism’s rules when establishing the territorial boundaries of our nonproprietary city. This means the nonproprietary city will be built on privately owned land acquired in the real estate market, which is paradoxical, but consistent at least with the idea of “Building the Structure of the New Society Within the Shell of the Old”.

I imagine a crowdsourced (and of course crowdfunded) effort. Participants in this swarm are understood to be playing a unicoalitional game. The object of the game is to acquire

- as much land as possible, and do it in a way that is

- as geographically concentrated as possible, and

- as contiguous as possible

Think of it this way: Each swarm participant is looking at the real estate market as a whole (eventually converging on one geographic area, per nonproprietary city, anyway). Each available property has surveyed boundaries and therefore has geometric properties such as area and perimeter, and distance from other parcels. At any given time (starting with the first land acquisition), the swarm has an already-acquired portfolio of land holdings that can be mapped. For each available additional parcel, we can calculate certain properties of the portfolio assuming the addition of that parcel. These parameters would include:

- total land area of the portfolio

- radius of the smallest circle that circumscribes the entire portfolio

- total perimeter of the parcels, minus whatever portion of each is the boundary between two adjacent parcels

In terms of minimax (or maxhi schema) approaches to optimization problems, we’re looking to maximize the first of these parameters and minimize the other two. In a lot of ways this has the look and feel of a Dan Gilbert style urban land grab, and may or may not run afoul of the law. One huge difference is the nonproprietary nature of a nonproprietary cities project. A defining feature of a nonproprietary city, as I see it—as I am defining it (as of this writing a Google search of the quoted phrase yields no results)—is radical transparency.

For starters, a nonproprietary city building swarm is not a secretive clique. Its existence is to be a matter of record, and so is its agenda. More to the point, it is to treat all data as nonproprietary, along the lines of a “T corporation.” This is important.

At some point, the development of the nonproprietary city will proceed from establishment of geographic extent to development. Since breaking new ground can be expected at the very least to promote sprawl, and is generally not the most responsible type of land use, this will probably involve more renovations than erections, with any of the latter hopefully occurring on sites of dismantled buildings beyond repair. In keeping with the principle of extreme transparency, the blueprints will be released into the public domain in either case.

One approach to urban planning might be the “pubwan” model that I described many years ago. It is based on a mixture of proximity modeling, preference ranking and Parecon-style assets/needs assessment.

Since the nonproprietary cities movement is working against both statism and capitalism, independence is needed not only from the services of local government, but also those of the private sector, at least when it comes to infrastructure. I propose a decentralized grid of local utilities, with each building, perhaps each household, being both a producer and consumer of such services as electric power, sewage treatment, solid waste handling, perhaps combustible gas from sewage and/or solid waste. Electrical and internet hookups could be house-to-house, resulting in a peer-to-peer network. Sewage treatment might take the form of septic tanks, only with outflow into the larger grid instead of dispersion into the ground as in low-density or rural areas. Another alternative might be a rotating biological contactor. Implementations of this technology are as small as filters for home aquariums and as large as installations in sewage treatment plants, so it seems plausible that the output of a household or small shop should be within the technology’s range of scalability. I’ve heard claims that water treatment systems based on living organisms can process all the way from raw sewage to safe drinking water, but I’m a little disappointed to see that the top search result on that topic is indeed a proprietary system.

Anti-statists sometimes refer to something we call polycentric law, or pluralism in creation and perhaps enforcement of laws. Nonproprietary cities might draw on polycentric infrastructure, as well as polycentric law. To the extent that polycentric utilities are metered, it would be at least as much for system tuning purposes as for billing purposes. Meter readings (probably automated using some form of “smart meters”) would be dumped directly into the public domain, in keeping with radical transparency.

Going beyond infrastructure into production and distribution of goods and services, I would suggest planning the local economy using the methodology of angel economics.

Aside from all this, it remains the case that the nominally private property comprising a nonproprietary city is still under the jurisdiction of one or more cities, townships, or counties. Taxes to those entities will necessarily be a drain on the local economy. This introduces another paradox in the site selection process in that there may be reason to prefer real estate in jurisdictions whose level of city services and corresponding level of local taxation is low. We may have to act like right wingers to live like left wingers. Such is life.

-

Quotebag #111

- TheLateThagSimmons:

- It’s funny how quickly the opposition will hide behind automation being a threat to replace low-end wage labor in relation to minimum wage laws, but then suddenly when we offer a different idea, they need those workers and the workers need their bosses.

- quoderat:

- One of the main reason “cloud” everything is being pushed is specifically because it makes things less secure. Always remember that.

- justamug:

- It is hard to come up with a simple rallying cry – although Death to the Market would do me.

- Cathy O’Neill:

- Since programming and mathematics themselves are not accessible to the average person, simply making the code available does nothing to prevent a black box.

- lucy mendes:

- First they came for the manufacturing base. Then they came for equity held in homes. Then they came for benefits and government pensions. Now it is subdivision of autos and spare rooms, and those hours spent underemployed and nervous, subordinated to task rabbit-ing.

-

Is earning an absolute prerequisite to giving?

I revisited a post at my other blog from a little more than a year ago. I also re-visited the Google Blogs search it’s based on, and I’m happy to report that Google Blog Search isn’t quite dead yet. I’m also pleased to find that the search (which I hadn’t visited for a few months) returned a couple of actually-relevant results I hadn’t already seen. These are:

- Case series – why and how to learn programming by Ryan Carey

- 10 Secrets You Should Have Learned with Your Software Engineering Degree – But Probably Didn’t by Andy Lester

- Philosophy vs. programming by Dr. Chris “Uncredible Hallq” Hallquist

The post by Ryan Carey is frankly a testimonial for yet another of those “coding boot camps” that have been popping up like toadstools in the last year or so,and should probably be taken with the number of grains of salt appropriate to folks out to sell you something. The post by Andy Lester is about pedagogy, not job hunting per se, but it seems useful as a guide to assembling a marketable portfolio of skills. The post by Chris Hallquist is actually interesting. The question is, is it interesting in a way that is relevant to my situation? Is it “news I can use?” From Dr. Hallquist’s post:

One thing to emphasize is the contrast in the job prospects of the average programmer vs. the average philosophy PhD graduate. I started my first programming job less than a month ago, and I was by no means any employer’s ideal job candidate, with no experience and an irrelevant degree. Nevertheless, I managed to land a quite high-paying job in San Francisco. It took four months of searching, which felt like a long time, but that’s nothing compared to the job search troubles many philosophy PhD graduates have. There’s nothing particularly special about me that got me here—it was mostly a matter of my having any programming talent at all (which, admittedly not everyone does).

I find this quite shocking. I went through a period from about 1990-2000 of trying to break into programming with about a .100 batting average for resume-to-interview and literally .000 for interview-to-offer, over easily hundreds of interviews. More recently, I have decided again to attempt to penetrate Fortress Employment, IT Division. I haven’t yet kicked my current job search into high gear, so I have no statistical sense of how much interest there is in me. So far I’ve mostly been building a portfolio and trying to learn what I can about the overall climate of the job market. I’m trying to figure out what factors might account for the differences between my experience with the J.O.B. market and Hallquist’s:

- Could the main difference (or even clincher) be the fact that Hallquist went to San Francisco? Almost all my job hunting has been local. Add to this that my home state (Michigan) has ranked in the bottom one or two states for employment statistics for decades, independently of the economic cycle.

- Is a PhD in philosophy a far more powerful credential than a BS degree in math?

- Could it be something like Chris being much younger than me? (which of course may or may not be the case)

- Is Chris significantly less introverted than I am, which is to say, less likely to “freeze” in J.O.B. interviews?

- Did Chris put all his eggs in the networking basket and none in the “help wanted” basket (closely related to above)

My best guess is that the first item on this list is the absolute clincher, but it could be a combination of factors not even on this list. As they say, your mileage may vary. The last item is also plausible as an absolute clincher, much to my dismay. For what it’s worth, surveying the job boards and the equivalent today has exactly the same look and feel as it did ten years ago or twenty years ago. One gets the distinct impression that entry level programming jobs either (a) don’t exist, period, or (b) are filled exclusively through non-published venues.

What’s even more interesting about Chris’ post is the rationale behind choosing a career in programming. In my case it’s simply something I enjoy doing, although the embarrassing fact of not yet having done it professionally leaves me wondering whether there’s something inside the black box of programming careers that I’d prefer not to know about. Chris is a philosopher; specifically an effective altruist. Basically, Chris has decided that making and donating money is a more effective route to changing the world for the better than doing whatever it is that professional philosophers do. This approach to change agency is referred to as “earning to give.”

Curiously, the appeal of earning to give is also one of the selling points in the salesy blog for the coding boot camp. I’m still not 100% sure I want to go into coding, but I know I’d better do something for money, and soon. I’m 100% sure I enjoy the subject, have a deep interest in the concepts involved, and a firmly held belief that programming has the potential to provide real solutions for real problems. But I have reservations, and my poor philosophical background notwithstanding, they at least seem to my untrained mind to be philosophical in nature. It seems apparent even from my outsider perspective on the world of commercial software design and web design that virtually all monetization strategies are based on assumptions that seem to be downright cynical. Maybe that means I’ve lived an overly sheltered life and just need to get over myself. But too many software or web monetization strategies look to me like the moral equivalent of stealing candy from a baby.

Curiously, the appeal of earning to give is also one of the selling points in the salesy blog for the coding boot camp. I’m still not 100% sure I want to go into coding, but I know I’d better do something for money, and soon. I’m 100% sure I enjoy the subject, have a deep interest in the concepts involved, and a firmly held belief that programming has the potential to provide real solutions for real problems. But I have reservations, and my poor philosophical background notwithstanding, they at least seem to my untrained mind to be philosophical in nature. It seems apparent even from my outsider perspective on the world of commercial software design and web design that virtually all monetization strategies are based on assumptions that seem to be downright cynical. Maybe that means I’ve lived an overly sheltered life and just need to get over myself. But too many software or web monetization strategies look to me like the moral equivalent of stealing candy from a baby. The “earn to give” principle, whether called that or not, is a subject I’ve been struggling with for a few years now. Few things in the media mock me as effectively as the Wall Street firms’ ads for retirement products (I watch a lot of golf on TV). The ones that feel the most like an indictment, not only of my life strategy, but even my life philosophy, are the ones that depict someone retired from being some kind of yuppie or professional/managerial elite, and who now has the luxury of pursuing an “altruistic” vocation or avocation such as teaching or the arts, and I think one commercial even referred to “ski bum” (altruistic because ski instructor to differently abled folks or something). Maybe the true nature of life is accurately depicted by the old right wing-ish saw about having to fill your own cup before being able to add to others’, but I can’t seem to shake that sneaky suspicion that “earn to give” is more about “buying one’s soul back.”

The “earn to give” principle, whether called that or not, is a subject I’ve been struggling with for a few years now. Few things in the media mock me as effectively as the Wall Street firms’ ads for retirement products (I watch a lot of golf on TV). The ones that feel the most like an indictment, not only of my life strategy, but even my life philosophy, are the ones that depict someone retired from being some kind of yuppie or professional/managerial elite, and who now has the luxury of pursuing an “altruistic” vocation or avocation such as teaching or the arts, and I think one commercial even referred to “ski bum” (altruistic because ski instructor to differently abled folks or something). Maybe the true nature of life is accurately depicted by the old right wing-ish saw about having to fill your own cup before being able to add to others’, but I can’t seem to shake that sneaky suspicion that “earn to give” is more about “buying one’s soul back.”I’ve only taken two undergraduate courses in philosophy, but to the extent that I’ve glommed onto a philosophical faction (or “school”?) it would be negative utilitarianism. Maybe I should look into this effective altruism. Maybe it would be less self-paralyzing for me and then I would be able to achieve some comfort in life, if nothing else.