Is there a public domain separate from the public sector? Is there any interest in applying pressure to the private sector for increased transparency and a less proprietary approach to data?

I ask this because when I check in on #OpenData as a Twitter hashtag, approximately 100% of the tweets describe some kind of activity that is being undertaken in the “open government” arena, or something about some local or national government somewhere releasing some dataset into the public record.

I ask this because I want to believe that the open data movement is currently concentrating on public sector data simply because that is the path of least resistance or, in practical terms, that is where the available data are, so those who have queries and algorithms to try out simply go where the data are. Another, more cynical-seeming possibility that occurs to me is that the open data movement is populated largely by people who see a place for proprietary data in the world, or see treatment by business of actionable data as proprietary, as natural, legitimate and perhaps inevitable. “Information wants to be valuable” and all that. Another possibility that has occurred to me is that open data is the new open source, and some percentage of the open data activity is essentially portfolio work undertaken in hopes of making a career of data science, with the candid understanding that information wants to be valuable, and frank acceptance that professional careers in data will inevitably mean non-disclosure agreements, non-compete clauses and other data siloing strategies.

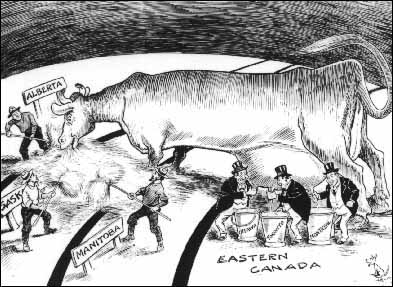

If there is some kind of career path from open data activism to information asymmetry-fueled careerism or entrepreneurship, then it is right and proper to view those who successfully make that transition as rent seekers, very much in the tradition of companies that stake intellectual property claims on things that are fairly direct fruits of public investment in basic research. If this is what’s happening, don’t be surprised if at some point these “activists” act to cut out the lower rungs on the ladder of their own ascent, perhaps by advocating privatization of those government agencies that supplied the open data they cut their teeth on, or alternatively, advocating “running government like a business” which of course includes recognizing data (which wants to be valuable) as a valuable asset and hoarding it (or at least pricing access to it) as a private entity would.

The main question on my mind is: Are there “rogue elements” within the open data movement that take a decidedly adversarial view toward commercial entities when it comes to matters of applied information asymmetry? #OpenData as a “brand” has become so absolutely synonymous with #OpenGov that perhaps I should be looking outside the self-identified open data movement for the “proprietary is a dirty word” kind of irreverence and spunk that I’m looking for.