David Brin, in a recent blog post, proposes that web browsing software be the locus of implementation for micropayments:

But back to my own obsession. Micro-payments. I have been poking at ideas with others, that boil down to this: we need a way for internet browsers to empower surfers pay a nickel for an article they want to read online. A one-cent or five-cent or ten-cent button that would let any of us hand over a small increment of value for something we choose to use for short time. (I wrote about this in The Transparent Society in 1997.)

Browser-resident payment sounds kind of creepy to me. I’m guessing (but only guessing) that implementing this is inseparable from including digital restrictions management (DRM) in the HTML standard. Unfortunately W3C seems to have caved in to Netflix (among others) and it appears some kind of DRM support will definitely be part of the HTML5 standard. Maybe my knee-jerk suspicion (actually rejection) of DRM makes me one of those clueless cypherpunks, but my cause here is open standards, not encryption (more DRM, of course, means more encryption). I don’t know how developed this idea of browser-based micropayments is. I’d be interested to see a run-down of how it’s supposed to work or an outline of its current state of conceptualization, if nothing else to (hopefully) disconfirm my suspicion that this is yet another attempt to write DRM into the protocols.

I think the future of journalism, if it is to have one, rests not in a more robust business model, but in self-removal from the business sector. Some use the term “intelligentsia” to refer jointly to journalists and educators. The education community (or industry, if you want to call it that) has traditionally straddled the public and nonprofit sectors. This is true of primary, secondary and post-secondary education. In the case of primary and secondary schools, the public school districts are essentially tax-collecting units of local government and the private schools are essentially non-profit organizations. Post-secondary institutions blur the lines between public and nonprofit sectors, as public universities rely on charitable donations for a large share of revenues, and are not generally tuition-free, while private universities rely in large part on taxpayer support in the form of student financial aid and research grants from governments. Recent years have seen aggressive incursions by the for-profit sector into both childhood education and collegiate education. I see this as a bad thing, for a number of reasons, but mainly because I view the body of human knowledge (“the literature,” if you will) as a shared heritage that must never become a commodity. While as a rule I see business as a lesser evil than government in some areas, the intelligentsia-related pursuits of education and journalism are on my short list of exceptions to that rule.

What then of journalism? A lot of the justification for the commercialization of education has exploited the widespread belief that the public financing model of education has failed, by leading to inefficiency, lack of accountability, civil service arrogance, and other supposed ills. The thing is that the for-profit business model of journalism that inevitably boils down either to selling a work product to an audience or selling audience eyeballs to advertisers and marketers, is in a state of failure, and no longer generates enough revenue to support serious journalistic pursuits. So far, the ideas on how to fix this have rested on the assumption that news will be distributed via websites and that like any web content, the key to profit will be monetization. The schemes currently on offer for monetization all appear to me to be pretty shamelessly opportunistic and cynical. To the extent that they involve advertising, it is increasingly the low rent variety, which in online advertising tends to the “weird old tip” genre of ad copy. Since ad blocking is pretty easy in the online world, monetization rests more and more on data mining in service to market research, which I find a little creepy, even though I accept that privacy is a lost cause. The thing that I find most diabolical about website monetization, at least in the case of hobbyist and other otherwise noncommercial websites, is the horror stories I’ve read about the revenues generated amounting to mere pennies, inevitably accompanied by a revenue floor below which the pennies can’t be claimed by their earners.

A better place for journalists, I think, is by emulating the role traditionally played by professors, described a few years ago in some admittedly somewhat cynical TIAA-CREF ad copy as “the greater good.” The problem with monetizing news stories is that in the digital age what you’d be monetizing is not copies of news stories but access to news stories. Once news is DRM restricted or otherwise monetized, there is a question of whether the receiver of the news is somehow bound not to share the text (or audio or footage) of a news story. In the days of printed newspapers, a copy could easily pass through many hands in the course of its date of publication, with portions sometimes living on for decades or even centuries as clippings. Whenever anything digital is monetized, the business model assumes payment on a “per use” basis. This is why many periodicals charge higher subscription rates to libraries than to individuals. If a DRM-restricted reader refers others to a news item, one assumes it will be as a link, probably parsed as a “teaser,” like the aggressive linkspam with text ending in ellipsis(…) that has absolutely swamped Facebook over the last two weeks or so. As Alex Tolley comments on the above-cited blog post (Wikipedia link mine):

One consequence if a micropayment model works, is that we may see more clickbait content as the economic driver is similar to the advertising model from the publisher’s perspective.

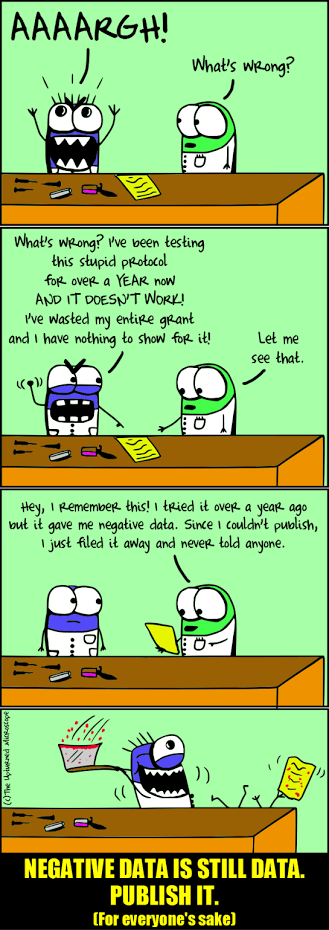

One thing I’ve always admired about the academic community is “publish or perish.” It’s an idea that is often criticized because research careers can perish for lack of publishing, which can have the negative consequence of people being drummed out of the profession for what may be political reasons, although it probably also has positive consequences of being a rough approximation of a performance standard. I endorse applying the “publish or perish” concept not (only) to the researcher, but more importantly to the research. I’m of the opinion that unpublished research (classified and/or proprietary research, as some academic freedom activists have correctly framed the issue) is either not real research, or is research that, instead of advancing the level of knowledge of humanity, turns the history of art, science and technology into a disinformation matrix. In extreme cases it might conceivably lead to a future in which the public is mystified by technologies it isn’t allowed to understand, making of society a cargo cult or perhaps something like Aldean culture.

I’m of the opinion that unpublished research (classified and/or proprietary research, as some academic freedom activists have correctly framed the issue) is either not real research, or is research that, instead of advancing the level of knowledge of humanity, turns the history of art, science and technology into a disinformation matrix. In extreme cases it might conceivably lead to a future in which the public is mystified by technologies it isn’t allowed to understand, making of society a cargo cult or perhaps something like Aldean culture.

News is history in the making. If there are not news providers of record (which to me means news content eventually being treated as part of the public record) then society possesses a memory hole. Not just the history of science and technology, but history itself, becomes a disinformation matrix.